Author: Dr Ashley Sparrow, Node Leader, Processes and Threat Mitigation

What’s the real issue?

As WABSI consulted with land managers and legislative regulators to explore what we still need to learn about management and conservation of biodiversity and ecosystems in WA, we discovered that the issue of a drying region is a priority concern to a wide range of stakeholders in the South West region.

This includes Natural Resource Management regions, the Department of Water (responsible for maintaining natural ecosystems that are dependent on water beyond incident rainfall), and the Department of Premier and Cabinet (as it plans the expansion of Perth whilst protecting ecological assets on the Swan Coastal Plain, through the Perth-Peel Green Growth Plan.

With a drying climate, wetlands and river systems in south-western WA face added pressure from demands on water supplies by agriculture, industry and domestic users) and urbanisation interacting with our drying climate.

Despite magnificent rains this summer, Perth for example, experienced a 10% decline in average annual rainfall since 1950 whilst in the Wheatbelt, the 225 mm rainfall isohyet has moved more than 150 km to the southwest.

More significantly for wetlands, average annual stream-flows in the Perth Hills have declined by about 75% in the same period – because of the non-linear relationship between rainfall and runoff – and recharge of groundwater has been affected to a similar degree.

There have already been some dramatic consequences of changed water flows. Extended drying of Lake Muir – a RAMSAR wetland – has led to soil acidification, a change that is effectively irreversible within a human lifetime.

How do we ensure a positive future for wetland and river ecosystems?

It may be impossible or too late to mitigate some changes, such as those at Lake Muir however, there are examples of positive interventions, including changes to local hydrology to maintain water flows. For example, the removal of weirs or capture of urban runoff where water can be purified and the translocation of threatened species over hundreds of kilometres, such as the Western Swamp Tortoise.

These interventions are not yet coordinated at a regional scale and thus it is not yet possible to determine whether we are already doing enough to ensure conservation of all water-dependent biodiversity for generations to come or whether additional efforts are required.

For example, if species translocations from one river system or wetland complex to a distant one are essential, how do different landowners, conservation groups and other stakeholders come together, what information would they require and what incentives are necessary?

This is a real opportunity for a regional, multi-stakeholder, adaptive management approach to solve this challenge – and for research to underpin such a joint effort.

Researchers ponder: What knowledge do we already possess and where are the critical gaps?

In response to end user concerns, WABSI facilitated a workshop of 20 researchers in February this year to begin to address the issue.

Participants, primarily biologists, were asked to summarise what we already know about water-dependent biodiversity responses to the recent and projected drying trend in the South West. They then discussed how existing knowledge could be used in a better way to enable end users and researchers to work together and maximise regional biodiversity conservation outcomes.

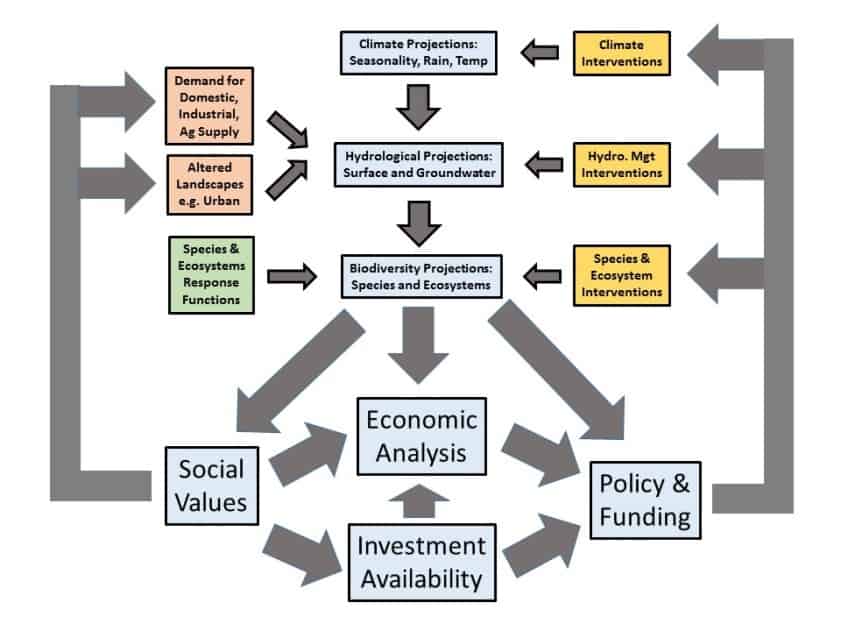

As the group considered the context in which environmental planning and biodiversity management decisions are currently made (as reflected in the diagram below), they agreed it would be valuable to consider our knowledge about bio-climatology (past and future), interactions between climate change and other environmental pressures, and the eco-hydrological vulnerabilities and levers in water-dependent ecosystems in Mediterranean climates such as in the South West.

More importantly, the group suggested testing the strength of current knowledge by trying to build a predictive model of climate change responses. This would use one or more species as an indicator to test resilience or vulnerability to varying levels of surface flows and groundwater.

Although such a model would not be perfect, it could a useful way for land managers and regulators to think about how we can better manage biodiversity conservation in a drying South West. In particular, the tool could prove critical in helping to prioritise what research is required to fill knowledge gaps so that more informed decisions can be made.

What next?

The next objective is to get a clearer picture of just how far our existing knowledge could be used hence, WABSI will bring together a more diverse group of researchers to see if projections can be made about the effects of a drying climate on selected indicator species. Subsequently, WABSI will bring end users into the discussions to determine what research is needed for a regional, adaptive management framework for our wetlands and rivers, in order to have a long term impact.

_________________________________________________________

Editor: Preeti Castle